How Platforms and Cities Unmade a Way of Thinking

Years ago I left academia – more specifically Asian studies. I had colleagues in Anthropology, History, Critical Theory, Comparative Literature, and Art History. It’s hard to express how much I miss these conversations. In the years since, working in Library Science, in tech, having friendships with artists and musicians…while adjacent, it hasn’t been the same. This is not intended to sound snooty or dismissive – there’s just a discourse that I’ve become estranged from. Book clubs come close, but they also cannot replicate it – for everyone arrives from different academic trajectories. They’ve read different histories, followed different canons. There was once a shared scaffolding that’s harder now to find. If I referenced Bourdieu or Debord there used to be an acknowledgement of that work and a shared understanding. Don’t get me wrong – our book club conversations are rich, varied, and deeply engaging, yet I sometimes I just miss discussions with people who shared the same class or curriculum.

When I follow academic blogs or accounts on Bluesky, I sometimes catch glimpses of these lost worlds. But they arrive as fragments: compressed, pithy, and often submerged beneath the urgency of current politics—which, while crucial, tend to flatten everything exhaustively.

While going through old files in preparation for our move, I’ve been finding printed correspondences with professors, colleagues, and others in my field from years ago. Reading them now, I’m struck by how many of those relationships were never continued. I pivoted from Japanese studies into Information Science, and then into tech, and my local circles became even further removed from that earlier intellectual life. I boxed that part of myself up. Revisiting it now feels bittersweet. This is not because the work was unfinished (I completed my degree, published in journals, published my thesis), but because the conversations were. I lost touch with that community and fell out of the loop. While my inbox still receives messages from a shared humanities listerv, lacking academic affiliations, I am no longer an active participant.

Substack promised a return to slower, more sustained thinking, but its design quietly undermines this possibility. Without robust ways to organize, label, or browse subscriptions by theme, the experience collapses into noise. Attention that wants to settle into deep focus is constantly disrupted by unrelated content. I used to rely on Feedly for precisely this reason: Asian Studies in one place, Digital Humanities in another, Information Architecture in another. These separations weren’t arbitrary, they were cognitive, they allowed immersion. On Substack, dozens of updates arrive daily in a single undifferentiated stream, making it impossible to read with care. The result isn’t abundance; it’s overwhelm.

Algorithmic platforms like YouTube or Instagram at least acknowledge how attention works, even if they exploit it. They detect patterns and narrow the field. Substack offers neither meaningful curation nor intelligent filtering – only a flattened feed that treats all content as equally urgent. Faced with that, I find myself reading less, not more.

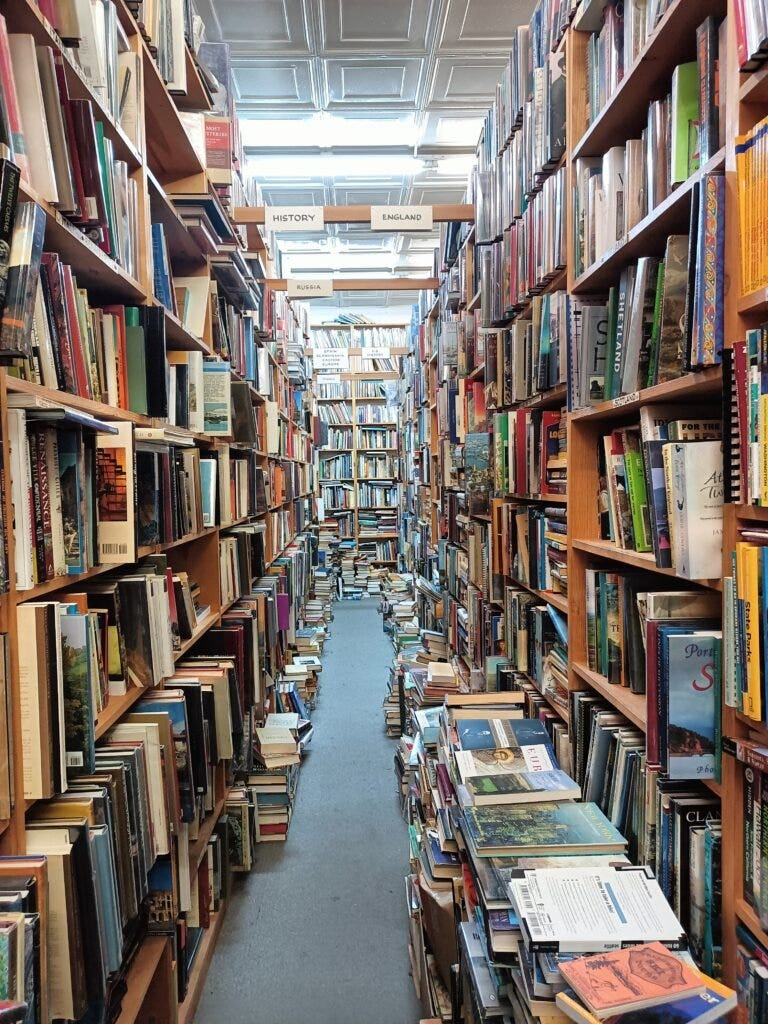

This mirrors, uncomfortably, the disappearance of the physical and social conditions that once made intellectual wandering possible at all. Walter Benjamin’s flâneur – the figure who roams city streets absorbing culture, ideas, and chance encounters – depended on an urban fabric that allowed for slowness, permeability, and unscripted exchange. Cafés near UC Berkeley once functioned this way: you overheard conversations about theory, politics, or art; sometimes you joined in; sometimes a single remark sent you down rabbit holes. A conversation about quantum mechanics might lead to a comic book touching on chaos theory and mythology, then to a used book on Jungian psychology at Moe’s Books, then to a European New Wave film at the U.C. Theatre. These experiences formed a chain – thinking unfolded across bodies, books, streets, and time.

Now that chain has been broken. Cafés became laptop farms, bookstores vanished or relocated to areas with less foot traffic, movie theaters became unaffordable or inaccessible. Online spaces, meanwhile, atomize experience into monetized fragments, interrupted by ads, paywalls, and notifications. Add to all this the inflated cost of American cafés – spaces where lingering without purchase is discouraged and conversation with strangers feels socially and economically improbable; the experience of a flâneur has been rendered structurally impossible.

What I’m grieving, ultimately, isn’t nostalgia or youth. It’s the loss of the environments – both digital and physical – that once made deep, meandering, non-instrumental thinking possible, and with them the quiet disappearance of the flâneur as a way of being in the world.

Notes:

If this piece resonated with you and you’d like to explore related work, here are a few places where I’m continuing these conversations:

- 💡 On Patreon, I share additional writing, behind-the-scenes notes, and works-in-progress that don’t always fit here. You can find it here.

- 📖 I also self-published my MA thesis on Butoh, which looks at performance, embodiment, and cultural history. If those threads interest you, it’s available here.

- 💸 And if a smaller, one-time gesture feels more your speed, you can leave a $3 tip via Ko-fi here. It’s always appreciated.