From smashed urns to marble surveillance cameras, Ai Weiwei’s Ai, Rebel dares viewers to confront systems of power. On view at SAM through Sept 7.h September 7, 2025

*Warning: this post contains imagery and references to strong language.

Now on view at the Seattle Art Museum is Ai, Rebel, a sweeping retrospective of over 100 works by exiled Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei. Spanning four decades, the exhibit is the largest U.S. presentation of his career to date.

Ai Weiwei is a provocateur—an agitator of political regimes and artistic traditions alike. One of the first things you encounter upon entering the show is a towering neon sign that simply says: Fuck (2000). Beneath it, a series of photographs depict Ai giving the finger to iconic sites of authority: Tiananmen Square, the Eiffel Tower, the White House.

In front of these images stand three gleaming sculptures of his upraised arm and hand, middle finger extended—Middle Finger (2000)—cast in gold and other luxurious materials associated with prestige and wealth.

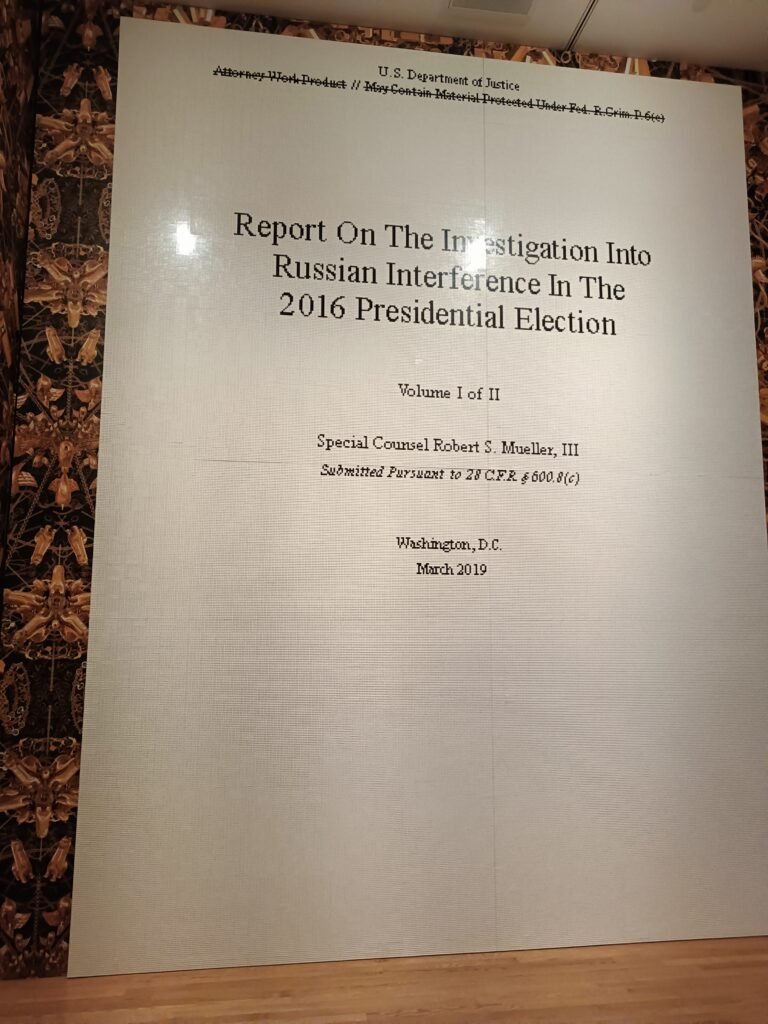

Ai’s practice spans sculpture, photography, video, and installation. But across these varied forms, a central theme emerges: the relentless questioning of power—be it the Chinese Communist Party, the institution of art itself, the machinery of capitalism, or even the American government. One of the most striking pieces in the exhibit is a monumental, floor-to-ceiling replica of the first page of the Mueller Report. In front of it sits a surveillance camera carved in marble, an elegant monument to the aesthetics of control.

“Everything is art. Everything is politics,” Ai famously declares. That mantra is not theoretical for him—it’s lived. Born in Beijing in 1957, Ai grew up in the far northwest of China, where his father, renowned poet Ai Qing, had been exiled during Mao’s Anti-Rightist Campaign. “The whirlpool that swallowed up my father upended my life too,” Ai once wrote, “leaving a mark on me that I carry to this day.”

Ai spent the 1980s in New York, absorbing the influence of Duchamp, Warhol,, and Jasper Johns. He returned to China in the early ’90s to care for his ailing father and became a central figure in the burgeoning experimental art scene. He co-founded the Beijing East Village artist collective, co-published books documenting their work, and later launched the architecture studio Fake Design. In 2000, he co-curated the infamous Fuck Off exhibition in Shanghai with artist Feng Boyi.—a direct rebuke to state-sanctioned art.

In China, Ai’s work increasingly took aim at government corruption and censorship. Following the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, which killed thousands of schoolchildren due to substandard building construction, he launched an independent investigation. He responded artistically by assembling thousands of children’s backpacks into installations that spell out haunting messages. At SAM, these backpacks appear suspended in the air, forming a serpent-like dragon—both memorial and protest.

In 2011, Ai was arrested by Chinese authorities and held without charge for 81 days, allegedly for tax evasion. A self-portrait of his arrest—meticulously assembled from Lego—appears in the exhibit, as does a full-scale replica of the prison cell where he was held.

At first glance, the cell might seem spacious by U.S. standards, with a table and adjoining bathroom. But the reality was grim: he was under constant surveillance, confined indoors 24/7, with two guards stationed inches from him at all times. He needed permission for basic actions, like drinking water. The light never turned off.

Also featured are some of Ai’s most iconic and controversial works. Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995) documents his deliberate destruction of a 2,000-year-old artifact—a symbolic challenge to the fetishization of cultural relics.

In Neolithic Vase with Coca-Cola Logo (Gold) (2015), he brands an ancient vessel with the Coca-Cola logo, merging historical significance with global capitalist critique.

Grapes, made of 26 hand-crafted wooden stools from the Qing Dynasty, speaks to the erosion of traditional life under mass production. These stools—once common in Chinese homes and passed through generations—have been replaced by cheap plastic imitations. The piece is both a lament and a celebration of communal memory.

In Forever (2003), Ai assembles dozens of steel bicycles—once a symbol of everyday mobility and collective identity in China—into a dense, architectural lattice. The bikes are uniform, industrial, and tightly interlocked, yet crucial steering mechanisms are removed. The result is a striking contradiction: an object designed for movement becomes rigid, static, and nonfunctional. More than a commentary on modernization and the decline of bicycle culture, the piece suggests a deeper tension—bodies bound together in shared purpose or system, yet stripped of direction or agency. It’s a haunting metaphor for life under authoritarian rule, where collective unity is enforced at the cost of individual will.

Throughout the exhibit, Ai Weiwei’s work insists on critical reflection. What does it mean to be Chinese under the CCP? What does it mean to exist within—or resist—global capitalism? Where do these systems conflict, and what do they conceal? Whether blunt or poetic, Ai’s art exposes the fragile scaffolding of power and the contradictions we’re often asked to accept.

Additional resources

The Seattle Art Museum has shared an interview with Ai Weiwei discussing his works, what it means to be a ‘rebel’, and why art is relevant.

Art Historian Rebecca Albiani discusses his biography and several of Ai Weiwei’s work for a talk for Horizon House.

Ai, Rebel is on view at the Seattle Art Museum through September 7, 2025—a rare opportunity to experience the full scope of Ai Weiwei’s fearless, boundary-breaking work in one place.